Here we will be social. We will share memories and experiences. We do not come here to vent or bash- just to schmooze…and enjoy the cookie parade.

Content will be uploaded regularly and reader submissions will be enjoyed.

All the Best!

Here we will be social. We will share memories and experiences. We do not come here to vent or bash- just to schmooze…and enjoy the cookie parade.

Content will be uploaded regularly and reader submissions will be enjoyed.

All the Best!

I recently had a memory of how many of our neighbors in 615 had a card table tucked away in a closet or behind a couch. Mostly Sharei Hatikvah people, but I am sure some Breuers people were card players as well. The table’s legs would fold under, and often a chessboard was part of the laminated surface. If we had occasion to borrow one of these from a neighbor, we knew we had to return it before a specific night. (Now, I had an aunt from my Polish side who was a big card player, but she just played at the kitchen table; she didn’t have one of these diddys.)

Another, perhaps more polished artifact of the homes we knew, was the Shabbos Lamp. I do not need to inform anyone reading this about this item, only that my father always wished he had one. He would reminisce about the one in his parents’ home, which – it seems was only used on Sukkos for some reason (this sounds extremely dangerous!)

In the early 2000s, I met someone who told me his father brought the family lamp with him on a business trip to China. He had 100 copies made and sold them for $100 each. Don’t worry, he didn’t ruin the market. Because they were not made of fine brass, but heavy metal painted in black or copper. I know, because I had my mother buy one for my father, and it weighs a ton. We revealed to my father the lamp’s inauthenticity, but he was proud of it just the same.

A series of Juden Stern stamps issued in Israel in 1981.

Now, a minute to reflect on the Besomim spice box. I know that all Jewish homes have one, but I also feel like the tower-with-a-flag box has a connection to us. Why? Because the famed Jewish painter, Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, would paint one into each depiction of the Jewish home. That and a Mizrach sign.

Are the Mizrach signs a particularly Yekkish home adornment? I would be naive to think so. But I suspect they are ubiquitous in our homes and appear only occasionally in others. Excuse my myopia.

But the Parshah signs are DEFINITELY ours, and ours alone. Again, this needs no explanation (see the picture) because they seem to be a staple. What needs explaining is why we have these? I believe it is a way to bring the Synagogue into the home. Something to change before Shabbos, like a Shammas would need to do in his Shul. I like to do it. We all like to do it. And the KAJ newsletter regularly has them for sale at the Shul office.

.

And that’s what I wanted to get to…

Every time I drive there, I know that this was Dad’s route during the years he worked for Bobby. I ordered one of his standards: apple strudel and coffee. (The strudel has changed.) Dad made his coffee extremely light and sugary, while mine was Darth Vader.

Anyhow, I assumed that the bakery staff was all new, but while sipping, the woman who was busy stocking the challah shelves strolled by me in a way that I realized she didn’t need to be in the seating area but wanted to catch a glimpse of me. Without any hesitation I said, “You remember my…” And she immediately finished my sentence. “He was such a good person. How is he?” Then corrected herself, “I know, I know…”

They didn’t have any of the (few) original Gruenebaum pastries that day, but the Challahs I brought home were phenomenal — and, believe me, I have shopped at every Brooklyn bakery.

There is a story here. Because Dad z’l would always rave about “Gruenebaum’s Challahs are the best in the world…” The rest of us would roll our eyes when he gave this speech. And – it turns out there is something to it! (I am referring to water Challahs. The egg was good as well, but not something unique.)

Friday after Sukkos, I brought home more of these for Shabbos (I was in Riverdale for a Levaya).

The Shabbos guests were equally impressed with these. I also brought home a ZwetschgenKuchen, which was delicious!

I will add a short story here from my book about my parents, called “Manny and Sylvia” and available on Amazon:

Finally, Grampa retired from the Transit Authority in 1998. This should have introduced an era of relaxation…but it didn’t.

Instead, after a full week at home Grandma couldn’t bear to see him around the apartment all day. It was January and Grampa ran into his old friend Bobby Gruenebaum at the bakery. “What are you doing home?”, Bobby asked. “I retired.” “You retired? So now you’ll come work for me!” And he did -for more than a decade.

There is a backstory here. When Grandma and Grampa were first married, Bobby asked Grampa for a loan, for which he would pay back by letting him take Shabbos challah, coffee and cake throughout the year until it was paid off. Grandma frowned on the terms of the loan, saying, “when you lend cash, you should ask for cash back”. The challahs don’t translate back into money in savings. But this is what Grampa did. This chesed planted seeds that would sprout many years later, as Bobby gave him a job when he needed it most! (Bobby was also a faithful photography customer all through the years, and he hired Grampa for all of his simchas!)

Grampa’s responsibilities at the bakery were varied. He would come at 5 a.m. to light the stove and take challah. He was a mashgiach at the Pesach bakery. He maintained the fleet of trucks and made trips to the bank and post office.

Thank you and Gmar Tov to all who read my things through the year.

One quick note on the Yoim Nora’im.

Many of us expatriated Yekkes can showcase our roots at this time through white ties and white Yarmulkas.

Someone in my neighborhood, whose father left the Heights as a teenager, wears his tie and Yarmuka proudly. He turned to me on Rosh Hashanah and asked why my Yarmulka is not white. In turn, I challenged him: “If this is so important to you, why could I not get you to attend our local start-up Yekke minyan even ONCE this whole year?” This ended the conversation. When I later asked him to join us on Shabbos Teshuvah, he had a bunch of excuses. So there are “Yekkes in white-yarmulka only.” (Something like the Kol Nidrei/Neiah Jews who once walked this country.)

Anyhow…in my childhood at KAJ I remember that many men wore a white cloth rabbinic-type Yarmuka that went with their Kittel. Some would just wear a white leather or velvet Yarmulka. Whatever they wore, the standard hat worn for davening was replaced with this Yarmulka.

My close friend, a grandson of Rav Schwab zt’l asked the Rav why we are not wearing a hat on these most holy of days!

Rav Schwab explained that these white head coverings, as they are explicitly worn to enhance Davening, satisfy the requirement for a special head covering.

I do not know if his answer “covers” the regular white Yarmulkas, or just the rabbinic type beanies that are used only in shul.

(I now explain to people when they talk about Yekkes and white Yarmulkas, that it is not a fashion statement, but a way to Daven- perhaps mimicking the angels who are described as “Ish Lavush Badim”, “the man in white linen”- and it is a replacement of the hat.)

Now, on the much-celebrated Yekke WhatsApp group, my old friend S. Katanka has posted a page from the Minhogim of Amsterdam, where it is stated explicitly that the white Yarmulke, if respectable, replaces the hat. (The author is upset over those who just wore their nightcap to shul!) Clipping below:

“Even on the High Holidays, it is forbidden to wear a white Kipah if it is not a garment of the Saregens”

Among my summer reading was the Dr. Moller bio; see my post (here).

We know, and it is well documented in the book, that Dr. Moller is a descendant of Rav Hirsch zt’l.

Some of the Klugmanns (all of them?) are also descendants.

Finally, there is a Hirsch family in Brooklyn and now Lakewood, with the names Hirsch and Eisenberg, who are direct descendants. (In my extended career as a Yeshivah Bochur, I dated one.)

One of the Brooklyn Hirschs was Naftoli Hirsch, who served on the board of the Jewish Observer. Another member of this family was canonized in a mildly famous story by Rabbi Pesach Krohn.https://aish.com/48906762/

Perhaps, as a community, we have missed out on knowing the “broader family,” and, in truth, some of these families have been separated from our mesorah for several generations already.

It has been suggested that the Breuer and Hirsch families have grown apart over time (besides reasons of geography) because the appointment of Rabbi Shlomo Breuer as a successor to Rav Hirsch in 1888 displaced the Hirsch children from the Frankfurt rabbinate. After the war, these families did not really reconnect in any meaningful way.

In any case, a few months ago, a friend directed my attention to the fact that a Hirsch descendant is buried right here on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn. The descendant is none other than Rabbi Yeshaya Levy z’l of the age-old Congregation Ohab Zedek on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Levy was only an associate Rabbi there. The main Rabbi was R’ Phillip Klein z’l, who was married to a daughter of R’ Mendel Hirsch z’l, the son of RSRH, who was once favored for the Frankfurt Rabbinate.

Some material about them is found in the comments section of Kevarim.com :

Rev. Isaiah Levy of the First Hungarian Congregation died at the age of 51, six years after arriving in America. A grandson of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, famous champion of Orthodoxy in Germany, he was born in London and received his education in Germany. During the war he was a chaplain in the Austrian army.

His brother, Isaac Levy, was a noted dentist in London, who translated Rav Hirsch’s commentary into English. Isaac’s son wrote an interesting memoir which tells much more about the family. There’s No Place Like Jerusalem by Samson Raphael Levy. Rav Shaye Levy was a rav who stood up for what was right and was not a crowd pleaser. He disapproved of the placing of the Amud for the chazan, so when he davened from the amud, he placed a shtender where he thought it belonged. He insisted that his community should have cholov yisrael milk and encouraged one of his children to open a grocery store on the West Side of Manhattan, specifically to provide cholov yisrael products. He was afraid that the long chazonishe davening would cause people to eat before making kiddush, so he made a minyan for shacharis in his home (which continued for many years under the leadership of his son Ellis). His encouragement of kvias ittim LeTorah is found in several published speeches.

More information about Rev Phillip Hillel Klein can be found in the comments on this page: https://kevarim.com/rav-hillel-ha-kohen-klien/

Stone of the Rebbetzin Julie Klein, daughter of Mendel Hirsch z’l/ The inscription mentions in bold how she passed away just two days after her husband!

Anyone who remembers my family will remember that Pesach always meant one of my uncles from Switzerland spending the holiday with us. My father had two brothers who never married. One looked just like my father. He was known for his clown antics but was also very serious and private. The other was lively and talked quickly, but he also suffered from nervousness, which always made his life turbulent. He, too, liked to be funny and had a kind heart. With all of his challenges, he ran a children’s magazine called Kol Hano’ar, which was popular in Switzerland. (My father would receive it and share it with Rav Mantel’s youngest son, who was still a boy when the Rav came to New York.)

The experience was always memorable. Europeans always have an air of sophistication compared to us Americans. Their clothing seemed fine. There was always a hint of cigarette and cologne. Our home was suddenly filled with the Swiss language, coffee was served constantly, and loud conversations—sounding like heated arguments to one who doesn’t speak the language—ensued.

Then came the antics—burping competitions after the meal, silly pranks, funny faces, and my mother chiding her brothers-in-law. Her favorite beef was how they always came with Swiss chocolate bars for me. Since Schmerling was readily available in our local grocery store, she would scold them for their lack of originality. Of course, they were bringing a whole stack of chocolates, much more than we would have bought—so there’s that.

Those uncles have long passed, and my father is not here to fight with them either. Yom Tov will come in with its memories, which the family holds dear and cherishes. The Seder is a link in a chain of Seders past and times separated from us by many Afikomens.

Good Yom Tov!

Featured image available here: ID 53007651 @ Catarchangel | Dreamstime.com

Hello all. I am sitting at my computer on what turned into a morning at home preparing class.

This past Shabbos was Rosh Chodesh, Shekalim on Parshas Terumah. This hasn’t occurred for some 31 years (Shekalim is usually on Mishpatim) and won’t for another 20 or so years. Friday Purim and an Erev Pesach on Shabbos (as we have this year) will not happen again until 2045.

I have mentioned my involvement in a local Minyan of Yekkes and Minhag Aschkenaz enthusiasts here in Brooklyn. We have been meeting on Friday nights and Motzi Shabassos. We occasionally meet for Shabbos morning as well, and we intend to hold services for the Daled Parshiyos. Although I thought I more-or-less knew the Minhagim of our Shul, it isn’t until I needed to implement them that I realized how many little things go into getting this right.

But here is a beautiful thing that I experienced recently. We, of course, make Kiddush and Havdallah in Shul. Recently, I used the alternative tune for Kiddush, the one composed by Chazan Abraham Katz of Amsterdam and used by Chazan Frankel for many years. It is a much slower and more ornate Kiddush, with deliberate and long elaborated syllables belted out fervently. As I deliver this Kiddush, I am overcome with the moment. With the many eyes focused on my Kiddush cup. With the sanctity of receiving the Shabbos day. With the song, I am singing for Shabbos in this Kiddush. I felt like I was delivering the Star-Spangled Banner in Giants Stadium. I felt the beauty of the community accepting Shabbos together in Shul over this one small cup of wine.

I remember how, in my youth, in the Breuers Shul, there were people who sometimes talked in Davening (as one may find anywhere). Not everyone stood for Chazoras Hashatz or Krias HaTorah. But Kiddush always commanded utter silence, and the entire shul stood.

An interesting point of order connected to Kiddush:

On Friday night, the Chazan makes Kiddush wearing his tallis, but on Motzi Shabbos, he does not put on a tallis to make Havdalah. I am informed that even if the Chazan was the Baal Tefilah on a Motzi Shabbos (for instance, if he is a Chiyuv), he removes it (!) for Havdalah.

I asked Reb Yisroel Sidney for some explanation.

He said there is no known reason why the cantor does not wear a Tallis when making havdala in shul. But that is the minhag. So much so that even if the Cantor prayed the evening prayer, he removed it for havdalah and shir Hamaalos.

I asked why Shir Hamaalos is sung from the Almemer.

He had two possible reasons. First, even though it already was part of the prayer, since they added a tune, they wanted to differentiate it, as is done on Friday nights, Lecha Dodi. Second, for reasons of practicality, since he is not the Baal Tefila (a member of the congregation after a Chiyuv davens Maariv on Motzi Shabbos), there would be nowhere for him to stand as he would sing it. The Baal Tefillah would have to step aside awkwardly.

In some shuls, such as monks in Golders Green, London, the person making the mourners kaddish wears a Tallis. This is supposedly documented as the Frankfurt custom.

Nevertheless, no one in our community whom he has spoken with who grew up in Frankfurt remembers that specifically being done there.

He also noted that in Frankfurt, Kiddush and Havdalah were done by the Shamash and not by the Chazan at all! (This would possibly explain the reason the Chazan does not wear a Tallis for Havdalah, as this was never considered the Chazan’s responsibility, but that of the Shamash in his capacity of tending to the “guests” (I.e., wayfarers who would sleep in the Shul when passing through a town in times of yore. They were part of the reason this Minhag started.)

Finally, Reb Yisroel noted that in Sharei Hatikva, where he grew up, one reciting Kadish would wear a Tallis as in Munks. Further, a mourner wore a Talis at Mincha and Maariv, even if he would not receive a kaddish, such as in the 12th month. For this reason, in his 12th month, he avoided going for those prayers because he found it odd.

Recently, I have been participating in a newly formed Aschkenaz Minyan in the style of our Gemran Mesorah here in Midwood, Brooklyn. The Minyan formed over the summer through the efforts of a good friend- a young man of Lithuanian descent who harbors a thirst for researching and reviving Minhag Aschkenaz through his blog, along with Moshe H. – a KAJMO expatriate who had first hosted the minyan in his home and was later instrumental in finding a dedicated space for the Minyan.

On the last days of Sukkos, the Minyan had all Tefilos, but since then, we have only been meeting for Friday night and Motzi Shabbos. This even though we have a Sefer Torah on loan from Yehudah N. and his family. We intend to meet for Shabbos Mevorchim Shacharis, but this has not materialized yet.

On Sukkos, I had the chance to sit in the Kehillah Sukkah next to Mr. Michael W., who told me he has access to a very old Sefer Torah from Germany that is Pasul beyond repair. I asked if I could borrow it for Hakafos, and he agreed. The Sefer was returned to his father upon the liquidation of Cong. Beth Hillel in the year 2000- although he does not know how his father initially got it to the Shul. The inscription on the Torah was hard to read since the name of the city is not found on any map. The year of its dedication is clearly legible as תרכט= 1869 !! Upon closer look and with the input of Yitzi E. it became apparent that the city is Berlichingen. This city is on a map and is home to a famous medieval knight whose life was memorialized in his autobiography (!) and by the German writer Goethe: Gotz von Berlichingen. Knights and castles aside, the town had a Jewish community dating back to the time when Gotz’s family still governed the district!

The following is from Geni.com

“Jews are first mentioned in records dating from 1632, when the village was ruled by the noble Berlichingen family and the Schoenthal Monastery. The Jews who were permitted to settle in the village were descendants of the Jews expelled from Spain. They were treated well but subject to paying high taxes. The congregation was established in 1632. A cemetery was consecrated that same year and also served the neighboring Jewish communities. Prayers were conducted in a private home; a synagogue was established during the mid-18th century.

The Jews worked as cattle, sheep, and fish merchants, as well as shopkeepers, peddlers, and moneylenders. Others worked as artisans, butchers, and innkeepers. Their activities during this time boosted the village’s economy.

The first rabbi of Berlichingen was Rabbi Jacob Berlinger (served 1809-1834), a descendant of Rabbi Akiva Eiger. During that period Berlichingen was the headquarters of the district rabbinate, which included three other nearby Jewish communities. Later the district rabbinate was moved to Bad Mergentheim. The community was led for many years by Shimon Metzger.

The Jewish population reached its peak in 1854, with 249 people (about 16.3% of the general population) living in the town, as well as a small group of about 50 Jews who lived in neighboring Beiringen. After 1883 the Jewish population declined due to emigration and the rapid urbanization in south Germany during that period. At the turn of the 20th century there were 90 Jews living in Berlichingen.”

Common Jewish surnames in the area were Kaufmann, Metzger, Gottlieb and Berlinger. The latter family produced several well-known rabbis and teachers. (From Allemania-Judaica.de)

The Torah scroll is enormous and was mine to hold as I danced and led the piyut “Besimchas Torah,” whirling in a circle with two other men holding their Torahs and this one retired Sefer Torah. A Torah that may not have had another Simchas Torah if not for our little Minyan.

The sukka at 615 West 186th Street was made of green aluminum walls that hooked into each other. It was originally a hut used as an office at construction sites (before trailers were invented?).

My father was most instrumental in retrofitting it to a sukkah.

He created a pully attached to its door to ensure it remained closed. He also steadied the sukkah by having the main Schach beams reach the walls of the building’s rear courtyards.

Mr. Adler owned a vinyl shower curtain and barbershop apron factory on Ft. George Hill. He would provide the sukkah with plastic tablecloths and window shades.

About a month before Sukkos, a “Sukkah meeting” was called in the apartment of one of the Frum residents. A date for erecting the Sukkah was chosen, and jobs were assigned. The last such meeting, and perhaps the only one I was old enough to attend, was in Benny E.’s apartment in the early 90s.

The young folk- (which included my father and Benny, as well as Mr. Zitter and several YU-affiliated families who passed through the building over the years) would assemble on a chosen Sunday morning to carry the Sukkah out of the building boiler room to the rear courtyard. The older neighbors (like Mr. Fulda-who had a watch repair shop on St. Nicholas Avenue, and Mr. Martin Lehmann, who worked for a butcher on the Upper West Side), would be given lighter jobs like bringing up the chairs and washing the walls with a garden hose.

The Sukkah could hold eight families at once and, in the building’s Jewish heyday, had two ½ shifts. The families who ate quickly and came home from Shul early were in the first shift. My father greatly disapproved of how these people ate their meals so quickly. As I remember, the Third shift had only one or two families—ourselves and the Zitters.

Shortly before Yomtov, the building youth would arrange to hang decorations, some from years past, and new homemade items such as paper chains and illustrations each year.

Entry to the Sukkah was via an alleyway or via a window in the building’s lobby, but the window required a short climb over a ten-foot drop.

The Sukkah was put out of use as the families in the building slowly moved out. My brother used part of it as his own for several years. Today, two small Schach rolls remain on my Sukkah as I write this.

Some Sukkah memories I have:

My mother knew Mr. Adler could not stand the smell of fried fish. To irk him a little, she would always serve this on one day of Sukkos.

My father’s birthday was at this time of the year. Some ladies in the building would grace the occasion by making him his favorite dessert: A German-style Linzer Torte. My father would rave about how intricate the process of baking this cake is and how many fine ingredients it contains. Because he cherished it so much, and it was so rich, we could all only have a slither of the cake, then it was committed to the freezer where it would wait to be eaten one slither at a time over several months.

For someone reading this who has never lived or eaten in a shared Sukkah, it is an experience of community and bonding. Of course, for us, it was the only way we knew.

On a discussion board this week with Yekkes in Eretz, a post mentioned the fact that many of our parents used nothing other than an apple dipped in honey for the “simanim” on Rosh Hashanah eve. Today, many of us have a variety of fruit and vegetable on the table and a placard from an institutional mailing, to help us through the various prayers.

What changed?

Mostly our awareness. Today, a person has access to many publications in the English language. People know the Halachos from several sources. People have more contact with other people and their Minhagim. Our approach to Mitzvah performance seeks to cover all the bases. Scarcity is more scarce. And all of the above.

But what I posted to this message board was that the Minhag—mentioned first in the Gemara—had been mostly forgotten by the masses until the appearance of the placards. The apple and honey were sufficient, and it was a special moment in the year—a savored moment—done with a simplicity that is not always found anymore.

Now, there was once a writer of Jewish sociological books, who wrote in an article (1990s) abot how he remembers a simpler time that people would buy candy bars based upon just reading the ingredients. The Jewish Observer roasted him for that line, since it is like longing for ignorance and folly.

But I know what he missed; perhaps he didn’t quite know how to express it.

He missed the innocence (or perceived innocence) of his childhood.

I recently saw an internet meme. It showed an old Blockbuster Video (rental store). The sign in front said: “It is not me, you miss. It is your childhood!”

All that said, the discussion went to which Siman to use first, which is a complicated sheilo in Halachos of Brachos. Many said that even with all the variety at the table, including fruits of Israel, the apple still goes first since it has precedence as “Chaviv”. The beloved fruit.

I smiled when I saw this. Seems I am not the only one missing my childhood.

Hello. Today, I am writing about Minhagim again. About the utopian Jewish dream of ending all minhagim.

Of course, this would refer to Yemos Hamoshiach. In Messianic times when the diaspora is gathered, there will need to be a merging of minhagim or a completely new order of Minhag for the united Am Yisroel.

The community of religious Zionists considers the establishment of the State of Israel to be a manifestation of the beginning of Messianic times. Thus, in the early years of the state, they embarked on making a uniting Nusach called “Nusach Achid,” initially attempting to make it the official siddur of the IDF.

To make a long story short…it never really caught on in Israel.

Despite the Olim’s philosophy lending itself to the idea of leaving the ways of the Diaspora behind, they nevertheless still had an affinity for the Nusach they brought with them.

S.Y. Agnon has a short episode in one of his lengthy books, which I enjoy recounting. It involves a pious man, a widower or a bachelor, who is introduced to a local widow in the Shtetl, and they decide to get married. The widow had already made plans to move to Jerusalem (as it was once a tradition for widows to live out their days in Jerusalem.) Having met this man, she would marry him, and they would go to Jerusalem together. Suddenly, a few nights before the marriage, he had a dream in which “Yom Tov Sheni” appeared to him as a woman – dressed in black and crying over the fact that he would no longer be observing the Yom Tov Sheni. He was so alarmed by the dream that he called off the wedding.

Of course, Agnon was poking fun at the Lilliputians and of the Shtetl life, but sometimes we, too, need to remember to keep our eye on the big picture.

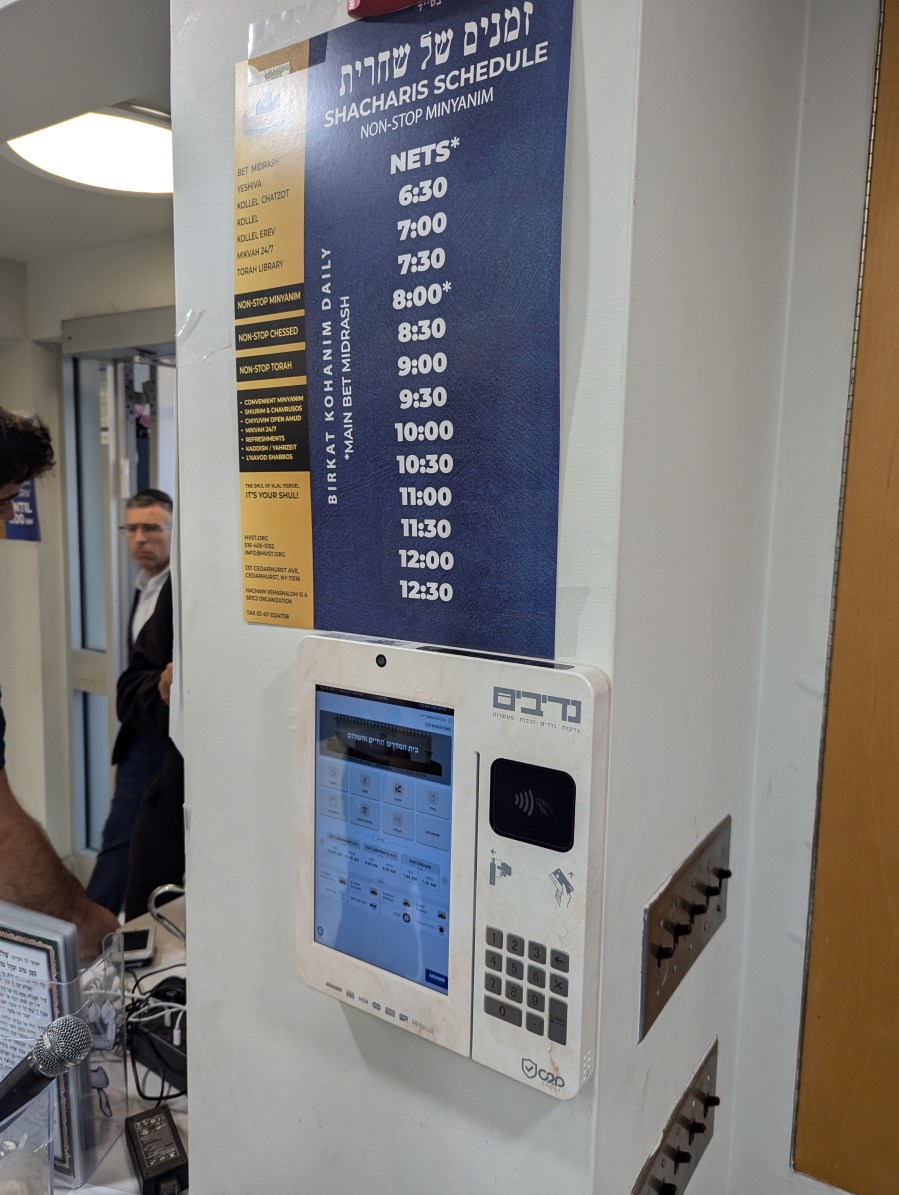

Well, this week, while davening Mincha in the Five Towns, I encountered a piece of the future. A “Minyan Factory”—or so I was told—has opened on Central Avenue.

I considered this a great convenience since other times I have ventured through that great avenue of Frum-commerce and Gastric sensations, I needed to find Mincha by searching in town for local Shuls and their schedules. Now, the Minyan would be “Central”.

Well, as I learned more about this “factory” I heard that it was started with the assistance of the Scheiner Shul of Monsey. Knowing this I understood that it would be the type of place that makes everyone feel welcome, embraced, and at home.

Indeed, there was a very welcoming coffee station, with soda, slushies, cake, pizza in a warmer, and hot dogs on rollers under a heating lamp!

Additionally, there were signs about regular shiurim and a most novel invention- that brings me back to the dreams of the early Zionists and their Nusach Achid:

There was a large dial on the wall before the Chazan’s Amud. It could be turned to indicate if the current Minyan was Ashkenaz, Sefard, or Sefardi. And what, you might ask, determines the Nusach of the Minyan? Nothing other than the volunteer Chazan of that Minyan!

The great Nusach Dial of the future!

Now, why would I, a guy with a Yekkishe blog that often glorifies Minhagim, be touting something like this?

As I begin to age, I start to look for ways that Moshiach could come amid all the craziness around us. I realize that while the Zionists initially hoped that the ingathering of the Exiles would produce a NEW Nusach, I can see in hindsight that the solution to finding a Nusach for our nation’s reunion after a two-millennia-long separation would be the inclusion of ALL Nuschaos, with a fluidity that would allow all Minhagim to find their home in Moshiach’s time.

Perhaps, this week, I witnessed the prototype of the Shul of the Future.